Modernist Maker 013: Unravelling a Century of Surrealism

For the 100th anniversary of the Manifesto of Surrealism, we take a look at surreal textile art...

Welcome to the Modernist Maker Digest 013! This month we look at how Surrealist artists used craft to create new worlds, from Dorothea Tanning’s soft sculptures to Meret Oppenheim’s furry fashion and Leonora Carrington’s magic tapestries.

But before we delve in, a little reminder that Decorating Dissidence aims to bring to life craft practices from across the twentieth-century to now – if this is work you’d like to support, as well as getting contemporary craft news, interviews and reviews, sign up below 👇

Surrealism: Existence is Elsewhere

It’s 100 years since Andre Breton published his first Manifesto of Surrealism and put surrealism on the map as a major avant-garde movement of the twentieth century. Breton wrote his manifesto as a reaction against the alienation his generation felt after the devastations of the First World War and living in a mechanised world. Surrealism aimed for a revolution in consciousness, by harnessing the power of dreams and the irrational. From its beginnings in Paris in 1924, surrealism went global and guided generations of artists seeking to subvert society’s power structures and reimagine the world.

In Breton’s surrealist group, women were objectified as ‘femme enfants’ (child women) – muses rather than makers of art. But many women drew inspiration from surrealist ideals and experimental methods to create powerful, radical works that redefined surrealism. To mark the anniversary of the Manifesto of Surrealism, we’re taking a look at how surrealist women artists used textiles and fabrics to take the movement in new directions.

Dorothea Tanning’s Soft Sculptures

“Maybe a pincushion is a far cry from a fetish. A fetish is something not exactly or always desirable in sculpture, being a superstitious if not actually shamanistic object; and yet, to my mind it’s not so far from a pincushion – after all, pins are routinely stuck in both…. [it’s] Not an image but bristling with images. And pins.”

Dorothea Tanning (1910-2012) began working on her soft sculptures in the 1960s, using fabric from charity shops that she sewed into strange, bulbous forms and stuffed with wool. Many of her monstrous soft sculptures offer a wry comment on the female nude, prompting us to look differently at traditional depictions of bodies in art history, typically viewed through the male gaze. Tanning’s sensual and strange body of textile art overturns stereotypes of femininity and domesticity by using these very tropes to transport us into an uncanny, nightmarish world.

Leonora Carrington’s Mystical Tapestries

Rebellious and determined, Leonora Carrington (1917-2011) resisted both the authority of her aristocratic family and the macho surrealist group. She fought hard to make art on her own terms, famously declaring ‘I didn't have time to be anyone's muse... I was too busy rebelling against my family and learning to be an artist’. Her inimitable otherworldly, mystical aesthetic unfolds across painting, prose, sculpture, textiles, and jewellery, in an emancipatory attempt to enchant everyday life via the language of dreams and visions. Carrington’s tapestries draw on the medium’s history of depicting myths and legends, but with a surreal twist. Carrington designed several tapestries for Monkton House, an English country home that arts patron Edward James turned into an uncanny surrealist spectacle with his fantastic collection of surreal art and design (most notably, Salvador Dalí’s Mae West Lips Sofa and Lobster Telephone).

Meret Oppenheim’s Furry Forms

Meret Oppenheim’s (1913 - 1985) interest in fur as a material of surrealist art stemmed from an evening at Paris hotspot Café de Flore with Pablo Picasso and Dora Maar in 1936. Oppenheim captured the imagination of Picasso and Maar with her handmade fur-covered bracelet, leading to jokes and quips about the potential for covering a range of objects in fur. When Breton invited her to take part in a surrealist exhibition a few weeks later, he offered Oppenheim the perfect opportunity to experiment further with fur. The outcome - a fur covered cup and saucer entitled Object - became a surrealist icon, its suggestive eroticism and uncanny visual effect perfectly encapsulating the movement’s ideals. It was the first piece by a woman artist to enter the collection of New York’s MoMA.

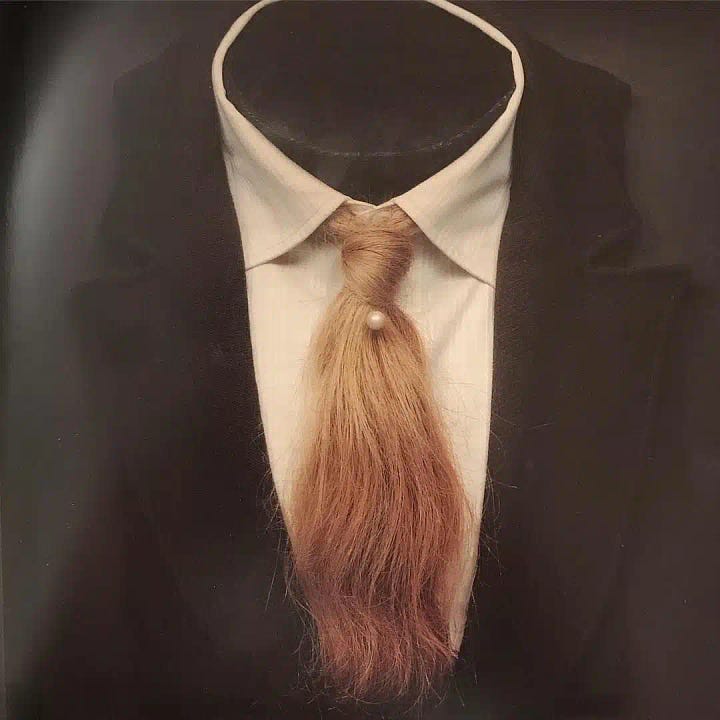

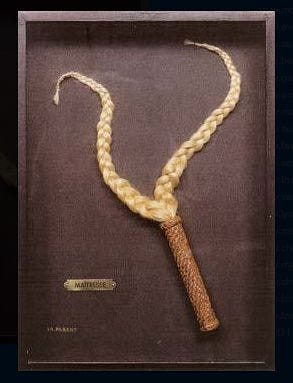

Mimi Parent’s Uncanny Hair Creations

Canadian born artist Mimi Parent (1924 - 2005) can perhaps be described as a second generation surrealist. She moved to post-war Paris as a rebellious young artist and soon befriended Breton and other surrealists, who had recently returned to the city after seeking refuge from World War II in New York. Parent’s theatrical, Gothic objects, collages, and embroidery added a new dimension to surrealist art; often featuring mythic goddesses, they demonstrate Parent’s interest in breaking gender binaries and instead creating a fantasy world where the masculine and feminine merged. Masculine-Feminine (1959), a tie made of Parent’s own hair paired with a suit, encapsulated this vision and was chosen by Breton to feature on the poster for the 1959 international surrealist exhibition in Paris. Maîtresse (1996), a whip in a box made of girlish blonde braids, troubles distinctions between hard and soft materials, power and vulnerability; it’s a surreal retort to the macho 1920s surreal ideal of the femme enfant.

Further Reading:

Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement – Whitney Chadwick (2022)

Angels of Anarchy Women Artists and Surrealism – Patricia Allmer (2009)

Surrealist Objects and Assemblage – MoMA (website)

Exhibition Review: Breaking Down Doors with Dorothea Tanning by Polly Hember (Decorating Dissidence, website)

Schiaparelli, Surrealism and the Society Woman by Olivia Bailey (Decorating Dissidence, website)

Gosh, that hair tie is so deeply unsettling. Love it!!